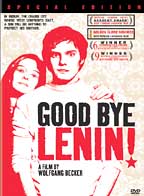

“Goodbye Lenin” is a film about the fall of the wall in 1989 and shows the historic events in the background of a personal story.

“Goodbye Lenin” is a film about the fall of the wall in 1989 and shows the historic events in the background of a personal story.

It is a wonderful and charming film, which explains a lot about the events in autumn 1989, how it came about and what followed afterwards. The personal story is a vehicle to transport how people in the East felt and dealt with the change, and how the change dealt with them.

In fact, it is a bit like a hidden documentary topped with a quite unbelievable personal tragi-comical story. The beauty lies in the contrast and honesty of describing the “real socialism” in the GDR and showing what it actually meant to people living in the system, and what it was later glorified to have been after the East has basically been taken over by the West and its capitalist values.

In this setup it reminds a bit of “Sonnenallee” and “Helden wie wir”, the other East German comedies, which focus more on the life in the GDR and its absurdities, this film focusses on the change. And how better can the change be described when having a static image of “East Germany” been brought in reference and relation to the “new system”. Systems are difficult to describe anyways, and the featured persons have been assigned different attributes on how to make the systems obvious for the audience. The mother is symbolising the old system- naturally, she has to die at the end- but beforehand she is trying to pull herself together, and reminding the audience of what positive features the GDR had to offer; the sense of community, the friendliness, and some quality products- if they were available; the absence of obvious greed; and the conviction of socialism in a stabilised and secured surrounding. But she also symbolises the big lie, that socialism was brought about by the fear of repression rather than real conviction, the restriction of freedom of movement, the fairytale news, symbolised by the blindfolding of the mother, so as not to allow anything to be seen that might upset her.

Alex, her son, is the nurturer, he has to find big strengths to hold up his mother, by bribing neighbours, appealing to their sympathy and using friendships. In a way, he symbolises the change- trying to connect and bring together the past with the present. Although it seems cruel sometimes, he is acting in the belief that he does the best for his mother, but also, it seems that, with time, he needs his very own version of history and socialism to comfort himself, and to build up his much more dignified and human version of a reunification, symbolised by the mother meeting her former husband and love again before she dies.

The enthusiasm and passion of the filmmaker makes the film charming and inspiring, the falling props and microphones hanging into the picture, make it even more sympathetic and passionate.

What is even more honest and amusing is the high discrepancy between the wishes of the participants of the peaceful revolution and what they actually got.

As in the beginning of the demonstrations, it wasn’t about Coca Cola and satellite dishes, but freedom, and the freedom of choice; however, only a few would have thought about losing their houses to a fresh, new western owner selling it away, getting unemployed or not being paid for months and piling on debts, which might have been even originated in the old system, but carried over, as e.g it happened to the farms.

In the times of East Germany, many films, songs and books worked on two levels- the obvious story, which was written for the officials, and the underlying coded message for the readers, which criticised the system in a subtle way. This film can be viewed very similarly, and the interpretation is up to you.

Of course reviews such as in the Guardian.. http://www.guardian.co.uk/arts/fridayreview/story/0,12102,1004944,00.html

“The sentimentality has less to do with politics, and more with nationhood and the great family of Germany. The Ossis are the naughty black sheep who strayed and are now forgiven. This was the triumph of the reunification at the time, and why Margaret Thatcher, far from welcoming German communism’s downfall, though it pretty dire news. And with the return of the fatherland comes the return of the father. When Alex’s runaway papa comes back from the west, Christiane is to reveal a terrible secret about communist sympathies being a sham, a lie, a symptom of denial, and about how her beloved communist authorities sabotaged her teaching career.

And so a pall of defeat and a sense of wasted lives hangs over Christiane’s story, for which her uneasy family reunion cannot quite compensate. Ostalgie becomes a terrible sickness, and a terrible sadness too.”

This actually reveals much more of the author and the Guardian than we actually would want to believe to be true. This is much more the attitude of a hidden wanna-be conservative than the libertarians we would like to see writing for the Guardian. And of course, if he justifies the success of the film with that conclusion, I wonder how it became a success then in East Germany?

For example, the claim that the Ossis would be “the naughty black sheep”, actually is already bang out of order.

Actually, there was not much choice for many of them, was there?

And we should also not forget that some of the beliefs of the roots of the East German system were built – at least temporarily on the belief to make things better, to improve.

The East German system was trying to build itself on antifascism- and it is a kind of how wrong it went so that far too many rebelled against the system by adopting a neonazi attitude.